પહેલું પાનું The Beginning

પહેલું પાનું The Beginning

Getting ready for Himalay treks

How to get information about treks in the Himalayas, which are “good” to do etc.? Before the internet?

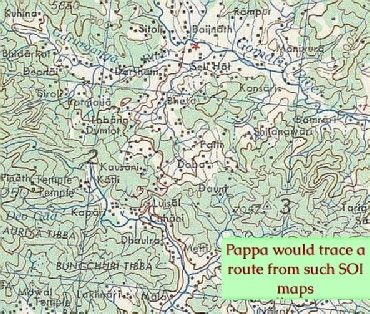

Bombay was unique in this regard. The Himalayan Club had been established in 1928. The Club spent Pre- which were freely available from Switzerland and were great for tracing routes for trekking. Pappa was a member of both Clubs, and knew everyone! A tradition started up in Bombay, that when expedition members went back – at least few via Bombay – they would be invited to give the community a talk about their experiences during the climb. A lot of information about the approach to the peak was precious for subsequent visitors and trekkers. In subsequent years, these talks were illustrated with slides of the climbs. The three of us never missed these talks.

which were freely available from Switzerland and were great for tracing routes for trekking. Pappa was a member of both Clubs, and knew everyone! A tradition started up in Bombay, that when expedition members went back – at least few via Bombay – they would be invited to give the community a talk about their experiences during the climb. A lot of information about the approach to the peak was precious for subsequent visitors and trekkers. In subsequent years, these talks were illustrated with slides of the climbs. The three of us never missed these talks.

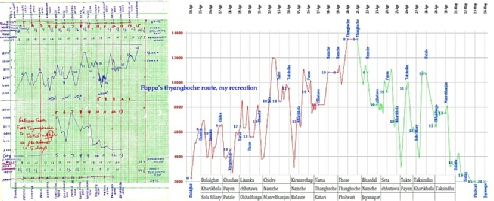

Pappa would come across some mention or reference to an interesting place either from someone in this group, or in one of the books someone had, or in the club libraries. And, off he would go chasing details. Either he would speak to the person who mentioned this new place, and ask for details, or chase reference in the article or book to get more details. When did someone travel to that place, where did they start from, what was the path like? Places to stay, buy food, guides, scenery, peaks to see, flora and fauna to note and so forth! He would cross check because one report quotes one name for a village, while another uses another name. He would try and get current status of roads, distances and number of days to walk. We typically did not walk more than 10 miles a day in the mountains, and only 8 if it involves steep climbs. He would then locate maps that show the entire route, and trace the route on tracing paper.

Once his mind was clear about the route,  he would try and locate a recent visitor and go meet them. The mountain addicted community in Bombay was small but close. Ask one person, and many would respond, with names, contact points and introductions. Once this route due diligence is done, he would determine the starting point as the last bus terminus in that road. Often – as in Nepal, since in those days, road and rail connections into Nepal were thin. We would need to identify the transfer stations for reaching the Nepal town to start the trek normally after a short flight from the border town where the railway terminated in the twin town in India. There was an all India train schedule compendium called a Bradshaw, which was essential to sort the train transfers.

he would try and locate a recent visitor and go meet them. The mountain addicted community in Bombay was small but close. Ask one person, and many would respond, with names, contact points and introductions. Once this route due diligence is done, he would determine the starting point as the last bus terminus in that road. Often – as in Nepal, since in those days, road and rail connections into Nepal were thin. We would need to identify the transfer stations for reaching the Nepal town to start the trek normally after a short flight from the border town where the railway terminated in the twin town in India. There was an all India train schedule compendium called a Bradshaw, which was essential to sort the train transfers.

Now pappa would start on the second part of the plan. In Indian Himalayas, the British had built a huge network – especially in remote areas – of “dak” bungalows and rest houses for different administrative departments: PWD (Public Works Dept.) and Forest depts.. They were all well-

Nepal was simpler, you stopped at a village, identified the largest house with a fair forecourt, and asked the owner for permission to stay the night! Never were we ever refused that welcome! The alternative in Nepal was to pitch tents near a good stream or even a trickle of water that the porters knew about.

The next critical activity was to book the train tickets, and get reservations in the newly started “sleeper” compartments. Pappa and I would go to the station at 4 a.m. to stand in the line. Reservations were easy in the beginning, but once the ticket agents and touts got into the act, it became quite difficult. We would line up exactly 3 months before planned departure date, because that is when the advanced reservations would be opened. There were times when we too had to go to ticketing agents (who were really bribe giving touts!) to get our tickets. Train transfers needed telegrams sent to the transfer stations, but one would not know the result till we landed at that station, ready for the transfer! Pappa would be rather anxious about these onward and return train reservations.

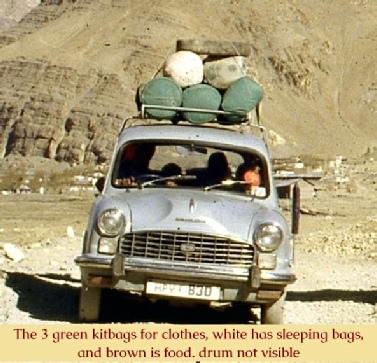

The next major job was to get our equipment ready! Get the kitbags repaired. A couple of canvas tailors at Pydhunie would have to be traced, and the repairs done. Our luggage and their contents was fixed. Four kitbags, one for cottons, one for woollens, one for sleeping bags (when we acquired high altitude sleeping bags – the first few treks till 1965 I think were with thick traditional cotton filled duvets!), The 4th kitbag was a bit different – it had zippers on the side, and was side loading one. That was the food kitbag. Why kitbags? Two reasons: one was the conserve weight because train tickets had weight restrictions, and second was the facilitate the carriage of our luggage by porters while walking. All food – grains, dried vegetables, various spices and condiments were double bagged, poly bags inside, cloth bags with draw strings outside. The last element was our kitchen drum! It was a large paint drum converted to our needs. It would contain 2 portable Primus stoves (real Primus brand folding stoves from Sweden), a dismantled pressure cooker with other basic vessels inside, other cooking accessories, and raw materials for one meal on the road! That’s it! Pappa’s and later my back packs were for energy snacks, cameras lenses, film and the binoculars.

Two reasons: one was the conserve weight because train tickets had weight restrictions, and second was the facilitate the carriage of our luggage by porters while walking. All food – grains, dried vegetables, various spices and condiments were double bagged, poly bags inside, cloth bags with draw strings outside. The last element was our kitchen drum! It was a large paint drum converted to our needs. It would contain 2 portable Primus stoves (real Primus brand folding stoves from Sweden), a dismantled pressure cooker with other basic vessels inside, other cooking accessories, and raw materials for one meal on the road! That’s it! Pappa’s and later my back packs were for energy snacks, cameras lenses, film and the binoculars.

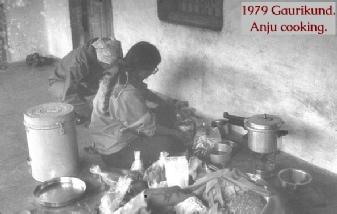

Food was an extended family affair. Latuben in Amdavad would dry coriander, ivy gourd (tindora) and fenugreek. Aunts would pitch in with energy snacks, while mummy bade the master energy snack – Pooranpoli! (quite a special Surat type recipe).

The medicine pouch was actually one my older aluminium school case, and it was my job to prep it for the trek. Throw out the expired stuff, and load up afresh. The bag went into the kitchen kit bag. The medicines were all over the counter stuff, ones that we would take ourselves if the need arose – which actually rarely did! Obviously we were no doctors, but villagers believe that “educated” city people know about medicines, and would request us to give them some medicine for tooth ache or fever or even a bleeding cut, because reaching a doctor would be a 2 or 4 day march! At the end of the trek, we would hunt up a doctor in the last town, and give all the meds we had to that doctor.

On the departure day – all the north bound trains left Bombay in the evening. We would reach the station at least 3 hours in advance. Since weight limits were in force, we would weigh all our luggage, pay the excess baggage if needed, and get the receipt for it. It was common for railway staff to board trains at minor stations, and ask to weigh baggage if seen to be plentiful. This was actually a scam because their equipment would have been doctored. The second reason of course was to store the luggage in the train properly before anyone else came to claim that space under the seats. One of my aunts would bring dinner for us, and it was almost always French bean dumplings in a ajwain (carom seed) broth, and pickled ginger fresh turmeric and chillies. We had an aluminium canister with a handle, which was normally the sugar pot at home, but did multiple duties on our treks, and has been possibly on all of our treks! The train dinner would be carried in that canister.

Pappa had a Kodak Brownie box camera when we went to Kashmir. I think he had had it for quite some time (because I found pictures he had taken well before his marriage!) 35mm film had not yet become popular, so 120 was “it”! He bought a Rolleicord next, and the invested in a Mamiyaflex with tele-

| planning |

| ઓળખાણ |

| લગ્ન પહેલાં |

| ૧૯૫૬ સુધી |

| મમ્મી પછી |

| હિમાલય |

| આખરે અમે બે |

| સંબંધો |

| તૈયારી |

| તિજોરીવાળા |

| શાહ કુટુંબ |

| મિત્ર મંડળી |

| ડુંગરાવાળા |

| ચકલાવાળા |

| ગઠિયા મંડળી |